View from Mt. Nebo

Madaba, Jordan makes a handy base for visiting the Jordan Valley from the eastern side of things. Mount Nebo, where Moses was allowed to see the Promised Land, is just 15 minutes away. In the early Christian centuries, a church graced the promontory, and its ruins, along with some incredibly beautiful mosaics, are a major tourist destination. Yet the main draw here is the view itself. Mount Nebo is as desolate a spot as you could find. But looking west, down into the valley and the hills beyond makes you appreciate just what is meant by the term "promised land." From this mountain top perspective, the entire verdant Jordan Valley is laid out like a banquet table.

With my nephew near the Dead Sea

The Jordan Valley seems comparatively lush, though the river itself is much diminished, primarily due to water piped to Israel. The area is agriculturally rich; thick with orchards, vegetable gardens, watermelon patches, grain fields, and surprisingly--banana groves. In fact, there are probably more banana groves than anything else in the valley, explaining their abundance in Jordanian and Syrian marketplaces. I have already touched upon my visit to the river itself in the previous post.

I allotted one day to visiting Mar Sabbas Monastery in Palestine, an isolated monastic community dating to the 6th century. According to the map I had, we could cross the Jordan River into the "West Bank" and then follow a road in a southwesterly direction which would take us to the monastery. But maps can be funny things in the Middle East. My map of Syria included Antakya (Antioch) and the province surrounding it, not recognizing the fact that it has been a part of Turkey since 1939. They likewise ignore the Israeli occupation of the Golan since 1967, and label the country on the other side as simply "Palestine." But Israelis hardly occupy the high moral ground when it comes to map making, either. I was provided a map in Israel. It made no distinction for the Golan, simply including it in Israel proper. But beyond that, we are used to seeing maps of the region that differentiate--to varying degrees--Israel from the West Bank. My map showed no such divisions--including the region within Israel and labeling it "Judea" and "Samaria."

I fully expected something of a hassle in trying to cross the border from Jordan into "Palestine." I wanted my nephew to have this experience, to give him a little better perspective on the way things really are in this part of the world. That said, it was an eye-opener for me as well. I had no plans to go to Israel itself; just cross over into the "West Bank," visit the monastery and return to Jordan. In talking with people back home, they seem surprised that I did not want to visit Israel. There are two reasons for this. First, a trip to Israel deserves a separate trip in itself. And second, I am a bit put off with the modern, secular state of Israel. Even before I became Orthodox, I never, ever bought into the whole premillenial dispensationalism/Christian Zionism that so many in America ascribe to. I wish Israel no ill-will, to be sure. But, the survival of the modern Israeli state has no more importance to me, religiously, than does the survival of Germany, or Bolivia, or Tunisia. There are many legitimate justifications to support Israel, but not the notion that we are somehow

helping God's plan. And for someone like myself, who has a tendency to become too wrapped-up in the political and foreign policy issues of the day, the whole Israeli-American relationship is irritating. I remain frustrated by the extent that Christian Zionism and the Israeli lobby have driven U.S. foreign policy in the religion for 60 years. Our current dilemma, as well as the plight of Christians in the Middle East, cannot be separated from this relationship. The sad fact is that one cannot really voice such opinions today without being label anti-Semitic, which I am decidedly not. But nevertheless, there it is. As it turned out, I was going to Israel whether I wanted to or not.

The fact is, the Israelis really do not want people crossing over from the east. The entire process was to take 3 hours. For starters, one cannot just drive across this border. So, we had to leave our driver, Mohammad, behind. While waiting in the Jordanian visa office, I was able to observe our traveling companions crowded into the small waiting room. These were primarily Palestinians who held other passports. Most had large families. That is one of the first things you notice in Syria, Jordan and Palestine--children are everywhere. I imagine that if they were traveling over here they would wonder where all the children were. One young Palestinian-American couple had 7 children, from about 11 years of age on down. They were thoroughly Americanized, speaking in English, unsupervised and being noisy, disruptive and somewhat bratty. The rest of the Palestinians, young and old, looked on in marked disapproval. We passed the first check point and were loaded onto a bus. There would be 6 more check points. For Palestinians without foreign passports, there would be 2 additional stops.

On the bus, I had an interesting exchange with an American contractor working with the State Department. With a diplomatic passport, he was able to zip on past us once we reached the first Israeli checkpoint. He had quite a bit to say in the short time we were together. First, he advised us (correctly) that the Israeli border crossing was a pain in the butt. Next, he told us to notice just how badly the Palestinians were treated in this process. He thought more Americans needed to get over here and see the situation first hand, instead of believing what they were being told back home. Then he talked a bit about Afghanistan, where he spent 2 years, and why we needed to be there, instead of Iraq. "Oh well," he concluded, "it's an Israeli war anyway." His job was to help train the Palestinian Authority security forces, "such as it is," he noted. He went on to add that he didn't see how the security forces were going to fight terrorism when the Israelis didn't even allow them to have bullet-proof vests.

The main processing center was at the 4th stop. Here, things bogged-down considerably. My Syrian visa was a red-flag, as was our plan for only a day-trip to the West Bank. Israeli security took my nephew aside and questioned him for an hour. I thought it would be a good time to catch up on my journal, which I carry in my back pocket. I took it out and began writing. An Israeli security officer came over, inspected the book and told me "no writing." Okaay.

A little relaxation in the Dead Sea

At the end of 3 hours, we were out the other side, where we met our driver for the rest of the journey. We were supposedly in "Palestine," but to this point we had seen no Palestinian officials whatsoever, only Israeli soldiers, security officers and drivers. Nor were we able to cut across Palestine to reach the monastery. The sleek, modern Highway 45 had us in Jerusalem itself before we knew it. The first sight one sees coming up out of the valley are the modern Israeli settlements on the hilltops flanking the highway. The look just like gated American suburbs. Pm a map, they appear as two giant lobster claws, encircling old Arab East Jerusalem. Peace talks come and go, but from what I saw, I don't believe Israel plans to give up an inch of Jerusalem. And "Palestine" remains a polite fiction.

Jerusalem itself has a Mediterranean feel--leafy, with lots of bougainvillea. I caught glimpses of sites I had seen on television: the Dome of the Rock, the old city walls, the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, etc. But we had no time to stop. Before I knew it, we were at The Wall, the monstrosity which allows modern Israel to deny--if only briefly--that there are Palestinians. One more Israeli check point put us out of Israeli Jerusalem and into Palestinian Bethlehem. From there, we were finally able to proceed to Mar Sabbas.

Washing in the Jordan

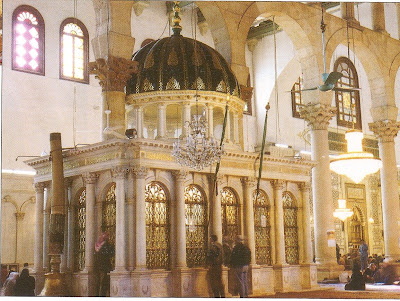

Mar Sabbas is not that far from Bethlehem, though it evokes a feeling of incredible remoteness. The monastery is on the side of a mountain, overlooking the Brook Kidron. My nephew and I arrived at the same time as a group of Greek pilgrims. In one sense, this was unfortunate. The monks knew we were American, but grouped us with the Greeks, to whom, of course, they were conducting the tour in Greek. I kept thinking the monk would turn to me and give a short explanation in English, but he never did. I particularly wanted to see the cell of St. John of Damascus, the patron saint of our mission church, but was unable to do so. My nephew had the better approach. He paid no attention to the group, or the monk who was speaking to them, but rather just stood back, venerated the icons, and better appreciated the sanctity of this very holy site. Visiting a chapel that displaying the skulls of the monks martyred by the Persians in the early 600s was a particularly moving experience. I counted more than 100 skulls, and I understand there are many more. When leaving, the monks did give us an English-language handout, describing the history of the monastery, which I appreciated. I had to remind myself that the monks were not there to provide tours for me, or to cater to my particular touristic needs, but rather, to pray for me, and all mankind.

Upon leaving the monastery, I thought it would be nice to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem on the way back. Only then did I learn that the Israelis close the border at 3:30 in the afternoon, leaving us only time to rush back to the crossing. We were the last vehicle through, and I was the last traveler to go through the border that day.

Greek Orthodox Church near the baptismal site

There are no easy answers when it comes to Israel and Palestine. Nicholas Kristoff, in today's

New York Times, has it about right,

here. Most American visits to Israel exist in an artificial vacuum, hermetically sealed from the surrounding environment and culture. Americans fly into Tel Aviv, are whisked down the modern highway to Jerusalem, and then bused around to the usual sites. They come nowhere near the West Bank, any Palestinians, or The Wall. And they return to the U.S., bubbling about how wonderful Israel is. They may have seen the "Holy Land" but they have not seen the Middle East. I am thankful my nephew and I caught a glimpse of it from the other angle.

Mar Sabbas Monastery, Palestine