St. Ephraim the Syrian is a favorite of mine among the Church Fathers. His writings continue to affect me in wonderful ways. I recently purchased a small book entitled A Spiritual Psalter, or Reflections on God, excerpted by Bishop Theophan the Recluse from the works of our Holy Father Ephraim the Syrian. I highly recommend it. I don't know how readily available the book is, but I do know you can purchase it from the St. Isaac the Syrian Skete here. I have copied a couple of examples from the book, below:

#41

Woe is me, to what judgement will I be subject, and of what disgrace am I worthy! My inner self is not like my outward appearance: I talk about how to fee oneself from the passions, but day and night I myself think about disgraceful passions. I conduct discussions about purity, but myself, I indulge in indecent behavior.

Alas! What trials await me? the truth is that I bear the image of righteousness, but lack its capacity. What face shall I who am guilty of such indecency wear when I approach the Lord God Who knows the secrets of my heart? When I stand in prayer, I am afraid gha fire will descend from heaven and burn me up, as it happened in the desert that there came out a fire from the lord that consumed the men who offered strange incense.

What can I expect, I who am weighted down with sucha heavy burden of sins? My heart is consumed with fire, my mind is clouded, righteous thougths have failed in me: like a dog do I ever return to my own vomit.

I have no boldness before Him Who will try my heart and inner workings. I have no clean thoughts, no tears while praying. Although I sigh and fall prostrate on my shame-filled face and beat my chest--this is a dwelling place of passions, a sweatshop of evil thoughts.

Thou knowest, O Lord, my passions hidden in darkness; the sores of my soul are known to Thee. Heal me, O Lord, and I will be healed. If Thou wilt not build the hourse of my soul, I labor in vain trying to build it myself.

It is true that sometimes I prepare myself to do battle with the passions when htey war against me; but the evil wiles of the serpent paralyze the efforts of my sould with sensuality and yield to them. Though no one visibly ties my hands, the invisible passions drag me away like a captive.

O Lord, enlighten the eyes of my heart, that I might rightly recognize the deceit and the malice of the passions. May Thy grace shield me, that I might be able to stand firm and resist, having girded my loins with courage.

Once Thou, O Lord, didst provide safe passage through the impassable sea for Thy people. Thou gavest Thy people who thirsted water out of a hard rock. Thou alone, according to Thy grace, didst save the one who fell in with theives. Have mercy upon me as well, for I have also fallen into the hands of thieves and, like a captive, I am bound by wicked thoughts.

No one is trong enough to heal the passionate temperament of my soul except Thou, O Lord, Who knowest the depths of my soul. Condescend and save me by Thy kindness!

and

#50

Have mercy on me, O God, according to Thy great mercy, and according to the multitude of Thy compassions, blot out my trangression. For if Thou wilt have mercy on me and free me from the pitiful affliction of the passions--if only Thou wilt have mercy on me, then will I willingly obey Thy grace.

If Thou wilt do this according to the greatness of Thy goodness, then wilt Thou deliver me. If Thou wilt pour out upon me Thy goodness, I will be saved.

I am certain that this is possible for Thee. I know that Thou hast forgiver and dost forgive all who turn to Thee with all their strength.

I confess that I have enjoyed the benefits of Thy grace many times already; but each time I have rejected Thy grace and sinned as no other has sinned.

But Thou, Who has resurrected the dead, raise also me who am deadened by sin. Thou Who hast healed the blind, enlighten the clouded eyes of my heart. Thou Who hast delivered Adam from the mouth of the serpent, pull me out of the mire of mine iniquities; for I too belong among Thy sheep, though I have by my own free choice become food for lions.

Sins have made of me a god; but, healed by Thy grace, I will become Thy son. I was thrown out like a corpse, but if Thou so desirest I will be brought to life.

I know that I have sinned consciously, but I have Thy saints to pray for me. I know that I exceed every measure with my sins, but Thy goodness is unsurpassable.

Thou Who hast preferred the publican, prefer also me, who recognize that I have done many more vile deeds than he. Thou, O Lord, hadst mercy on Zacchaeus who was unworthy. Likewise have mercy on me who am also unworthy.

Paul was once a wolf, and chased the sheep of Thy flock; but according to Thy grace he became a pastor who diligently cared for the sheep.

I know that he sinnes in ognorance, and that he was vouchsafed forgiveness of his sins and much grace because of his ignorance. But Thou, O Lord, condemn my sin committed in knowledge, and have mercy on me according to Thine exceedingly abundant grace.

Common-place Book: n. a book in which common-places, or notable or striking passages are noted; a book in which things especially to be remembered or referred to are recorded.

Friday, March 24, 2006

Thursday, March 23, 2006

A Fool for Christ (continued)

I try to read the New York Times whenever I can. I often differ with their positions, but for better or for worse, they still frame the debate in this country. I can support wholeheartedly, however, their stance in today's editorial about the Afghani on trial for Christianity (see previous post). You'll find no mealy-mouth platitudes, here.

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

A Fool for Christ

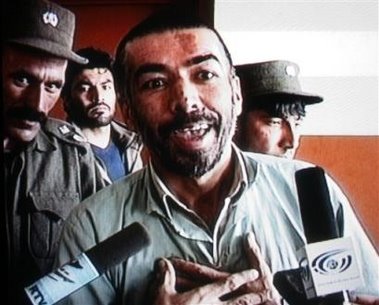

Before you get too comfortable with the status of the new Afghani democracy, you might want to read this. It seems Abdul Rahman is on trial, facing a death sentence for the greatest crime one can commit in Afghanistan. That's right, Abdul Rahman is a Christian. He even confessed to his crime: "They want to sentence me to death and I accept it, but I am not a deserter and not an infidel. I am a Christian, which means I believe in the Trinity."

The Afghani government--desperately seeking a way out of this public relations nightmare--has hit upon a solution: declare Rahman insane, as no Muslim in their right mind would convert to Christianity. "We think he could be mad. He is not a normal person. He doesn't talk like a normal person," prosecutor Sarinwal Zamari told The Associated Press. But this isn't anything new--as St. Paul noted, "we are fools for Christ" (1 Cor. 4:10).

The charges would be dropped if only Abdul would renounce Christ. The prosecutor, Abdul Wasi, said he had offered to drop the charges if Mr Rahman converted back to Islam, but he refused. "He would have been forgiven if he changed back. But he said he was a Christian and would always remain one," Mr Wasi said. "We are Muslims and becoming a Christian is against our laws. He must get the death penalty." At least give the prosecutor credit for being honest. There is no way Western apologists can put a smiley face on that kind of statement. Of course, this reminds me of the innumerable accounts of the early martyrs. All they had to do was deny Christ before their Roman accusers and their lives would be spared. Invariably, they refused to do so.

For an always colorful discussion of this and other Middle Eastern outrages and absurdities--but from an Egyptian perspective--check out Sand Monkey here.

For a courageous commentary on this issue, and the plight of Christians in the Middle East in general, from a Jordanian Christian read here.

And say a prayer for Abdul Rahman.

Friday, March 17, 2006

Open at Both Ends

Flannery O'Connor, who always had a way of getting to the heart of things, once observed that "one of the good things about Protestantism is that it always contains the seeds of its own reversal. It is open at both ends--at one end to Catholicism, at the other to unbelief." I have come to agree with O'Connor--that Protestantism is inherently self-destructive. This may seem a strange notion, living as we do in the Land of the Megachurch. But historians, I suppose, take a little longer view of things. Anyway, for a good read on what is going on in Evangelicalism today--and a fine example of the last part of O'Connor's statement--read the review of George Barna's Revolution in Christianity Today here.

I am particularly struck by this disturbing paragraph from the article:

Churching Alone

Still, Revolution's emphasis on personal choice would make a marketer rejoice and an apostle weep. Barna expects to see believers "choosing from a proliferation of options, weaving together a set of favored alternatives into a unique tapestry that constitutes the personal 'church' of the individual." The phrase "personal 'church' of the individual" must be the most mind-spinning phrase ever written about the church of Jesus Christ. Could it be that we evangelical Protestants, who have done more to fragment Christendom than any other group, are now taking that to the logical extreme: a church at the individual level, each person creating a personal "church" experience? At any other point in church history, "personal church" would be nonsensical. In today's America, it's the Next Big Thing.

On the Road—Part 4

Occasional thoughts on my spiritual journey

In my previous installment on this topic, I related my first exposure to the Orthodox faith during a 2003 trip to Bulgaria. Upon return to the US, my life quickly resumed its familiar pattern of work, home, and church. Things rocked along much as they had before--that is, until my encounter with the Church Fathers.

Above all else, you could characterize me, my wife and my son as readers. One cannot sit or lie down anywhere in our home without being within arms reach of a book, magazine or newspaper. Our bedrooms are no different, with books stacked on the floor and nightstands. And that’s the way we like it. About two months after my return, I was sleeping in our son’s bed, as we had overnight company who were using our bedroom. I reached underneath the bed to extract a book to read before going to sleep. What I pulled out was a small volume entitled Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers. I remember buying the book at a used book store about 15 years earlier, but had never gotten around to reading it. I suppose I was ready for it now.

I chose the section on Ignatius, probably because it consisted of only 7 short letters. As a history major, it is somewhat embarrassing to admit now that I really knew nothing of the man. In the short introduction to the letters, I learned that he was the third bishop of Antioch; had been so from about 69 AD; and penned these letters on his way to martyrdom in Rome in 107 AD.

Yet even this biographical information was challenging to my own particular religious presuppositions--for I was a Protestant of the Restorationist persuasion. Briefly put, we subscribed to the “great apostasy” view of church history. Adherents believe that the church went into a steep doctrinal tailspin soon after the death of the last apostle, John. Although pockets of “New Testament Christians" were supposedly in evidence throughout the ages, things basically continued to deteriorate until the Reformation, which saw a partial recovery.

But while we saw the Reformation as corrective, we viewed it as incomplete, a half-measure, as it sought only to reform, rather than restore the church to its New Testament purity. This view remains distinctly ahistorical, seeing the church as being above history and not being subject to historical forces; that it could be “restored” at any time using the “blueprint” of the New Testament. This restoration had to wait until the early years of the 19th century, however, when American frontier revivalists initiated what we referred to as “the Restoration Movement.” So, after 1700 years or so, it would seem that someone had finally figured out how to interpret the Bible correctly. Now, I say that a little facetiously and I realize that I am painting with a very broad brush here. Many sincere, faithful Christians in Restorationist churches today would scoff at this simplistic view. Indeed, perhaps sensing the inherent fallacies in the argument, most of the churches are downright sheepish about using this terminology anymore. And yet, this view accurately describes how Restorationists see themselves in history and remains the foundational understanding which under girds all these churches and sets the parameters for the way they continue to “do church.”

The Restoration Movement was very much a product of the American frontier, drinking deeply from prevailing concepts of liberty and individualism and being nourished on the tenets of the 18th century Scottish Enlightenment. They were confident that the intelligent, sincere inquirer could open his Bible, and with logic and rationality, deduce what God wanted him to do. They could avoid all the fractious, bickering denominations and become simply “New Testament Christians." From this vantage point, the early leaders gleaned from scripture that the "first century church" was autonomous in its governance, with each local congregation being led by elders, and being served by deacons, with emphasis on the priesthood of all believers. They perceived no organizational structure beyond the local congregation. The historical development of a hierarchy culminating in the papacy (and they had no concept of developments in the East as being anything separate and apart from Catholicism), was nothing more than the fulfillment of the prophetic warnings of Paul. This was our basic view of church history and when we read the pages of the New Testament, this is the church we saw.

This brings me back to Ignatius and his letters. For the church he quite plainly described was not this church. As Paul, the scales literally fell from my eyes. While I often have trouble remembering names, I am pretty good with chronology. The fact that Ignatius wrote these letters in 107 AD is not in dispute. This means, that to a large degree, his life overlapped the ministry of the Apostles. So, even though the date is 107 AD, this is clearly “first century” stuff. Ignatius’ church was one of bishops and clergy and deacons and laity. The unity of the church was his greatest concern as he approached his martyrdom. He admonished the churches at Ephesus, Magnesia, Trallia, Rome, Philadelphia and Smyrna to be united in Christ; to be submissive and obey their bishops, indeed to “be as submissive to the bishop and to one another as Jesus Christ was to His Father, and as the Apostles were to Christ and the Father; so that there may be complete unity, in the flesh as well as in the spirit.” He spoke freely and with warm, collegial affection for the bishops in these other cities.

Now the Restorationist would have a ready answer for this. They would say that this development was indeed the apostasy that Paul had warned about—the whole “wolves in sheep’s clothing” thing; an apostasy from “simple New Testament Christianity" into a hierarchical power structure. But this response is woefully inadequate. For the general view is that this digression evolved slowly over time. Ignatius was a contemporary of the Apostles. The fact that he served as the third bishop of Antioch from 69 AD to 107 AD places him squarely in the Apostolic age. So, the system of bishops, clergy and deacons were solidly in place by the end of the Apostolic era, rather than a digression that occurred after the Apostles. And if this system was heretical, as Restorationists maintained, then where was the outcry? Where were the voices of opposition? There were none. In fact, the “first century church" understood itself the way Ignatius described it. To be sure, there were schismatics, but they were, as Ignatius related, those who “denied that the Eucharist is the self-same body of our Saviour Jesus Christ.”

The bottom line is this: the church of Ignatius’ day--who studied at the feet of the very Apostles of Christ, who were part of the very same culture, who spoke the same language, who lived out their lives in that particular part of the world, who faced martyrdom for their faith-—understood scripture and Apostolic teaching one way. The church of the American frontier—separated by 1700 years and thousands of miles, a product of the western European Protestant Reformation, endued with the tenets of the Scottish Enlightenment and American pioneer individualism, reading English bibles translated from Latin bibles translated from the original Greek—understood scripture another way. Which had more credibility? Put in this light, the answer seems obvious. And yet I often heard it remarked in bible studies that we were much better off than the “First Century Christians," since we had “the word,” meaning of course, scripture and they didn't (Imagine that, having only the Apostles and their teaching!) That statement always bothered me, but only in time did I come to realize the misguided arrogance, and ignorance, behind it.

Frankly, the issue of church governance and authority was not “the” issue with me. But this raised a question in my mind that refused to go away. If we were so decidedly wrong about this, if our reading of scripture here was so fractured by the prism of our Protestant presuppositions, then what else did we have wrong? The question became for me, what do I do with this new insight?

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Interview with Dr. Wafa Sultan

Today's NYTimes carries a fascinating story on Dr. Wafa Sultan, a Syrian-American psychiatrist. A recent interview on Al Jazerra TV has made her something of an international sensation. She is being hailed by many as a much-needed voice of reason from the Islamic world. Others are denouncing her as a heretic, deserving of death. A passage from the story follows:

Perhaps her most provocative words on Al Jazeera were those comparing how the Jews and Muslims have reacted to adversity. Speaking of the Holocaust, she said, "The Jews have come from the tragedy and forced the world to respect them, with their knowledge, not with their terror; with their work, not with their crying and yelling."

She went on, "We have not seen a single Jew blow himself up in a German restaurant. We have not seen a single Jew destroy a church. We have not seen a single Jew protest by killing people."

She concluded, "Only the Muslims defend their beliefs by burning down churches, killing people and destroying embassies. This path will not yield any results. The Muslims must ask themselves what they can do for humankind, before they demand that humankind respect them."

For the rest of the article go here. I recommend it.

Perhaps her most provocative words on Al Jazeera were those comparing how the Jews and Muslims have reacted to adversity. Speaking of the Holocaust, she said, "The Jews have come from the tragedy and forced the world to respect them, with their knowledge, not with their terror; with their work, not with their crying and yelling."

She went on, "We have not seen a single Jew blow himself up in a German restaurant. We have not seen a single Jew destroy a church. We have not seen a single Jew protest by killing people."

She concluded, "Only the Muslims defend their beliefs by burning down churches, killing people and destroying embassies. This path will not yield any results. The Muslims must ask themselves what they can do for humankind, before they demand that humankind respect them."

For the rest of the article go here. I recommend it.

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

The Great Canon of St. Andrew

I am currently reading through The Great Canon of St. Andrew in Frederica Mathewes-Green's The First Fruits of Prayer. Thanks to Jim over at neepeople for a great link to an interview with FMG about the book here. Also, Gabriel has a very good link to the Canon here.

I particularly like the following exchange from the interview:

7. Is this the kind of spiritual writing that makes converts, or do you have to be pretty intensely prayerful already to get into it?

I think there was a time when this kind of writing made converts — when hard-edged challenges broke through defenses, and led from sudden tears to joy. Recently, we’ve been in a culture where "Pal Jesus" was mostly in the business of emotional reassurance. I see a new interest, however, in "grown-up" spirituality, that grapples honestly with the unspoken loneliness, despair, and fear right under the smiley-face surface. This is especially true of people younger than the Baby Boomers. I hope that the Great Canon will surprise some readers by confronting them with a side of Christianity they don’t often see these days, one that is simultaneously tough and healing.

I think FMG may be on to something here. We Baby Boomers have always been into comfort and reassurance. The younger generation may be ready for, as she says "grown-up" spirituality.

I particularly like the following exchange from the interview:

7. Is this the kind of spiritual writing that makes converts, or do you have to be pretty intensely prayerful already to get into it?

I think there was a time when this kind of writing made converts — when hard-edged challenges broke through defenses, and led from sudden tears to joy. Recently, we’ve been in a culture where "Pal Jesus" was mostly in the business of emotional reassurance. I see a new interest, however, in "grown-up" spirituality, that grapples honestly with the unspoken loneliness, despair, and fear right under the smiley-face surface. This is especially true of people younger than the Baby Boomers. I hope that the Great Canon will surprise some readers by confronting them with a side of Christianity they don’t often see these days, one that is simultaneously tough and healing.

I think FMG may be on to something here. We Baby Boomers have always been into comfort and reassurance. The younger generation may be ready for, as she says "grown-up" spirituality.

Friday, March 03, 2006

The Return of the Suriani

One of the best books I've read in recent years has been William Dalrymple's From the Holy Mountain: A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East. The author journeys among the diminishing and beleagured Christian remnant--largely Orthodox--in the Middle East. From Mount Athos to Constantinople to southeastern Turkey to Syria to Lebanon to Palestine to Egypt; none of the situations was as dire as that of the Syriac Orthodox Christians in southeastern Turkey. Some 200,000 lived in the area in the late 1800s, but their number had been reduced to about 900 by the time of Dalrymple's visit in 1994. A few tenacious monks hung on for the remaining families, but the author predicted that these would be gone in a generation. The Syriac Christians received no help from the Turkish goverment, as Kurdish guerilla groups saw the Christian minority as easy pickings. The Syriac Christians abandoned whole villages in the face of the Kurdish attacks. The Christian goldsmiths and silversmiths--who had been renowned for hundreds of years in Mardin and Midyat--closed their shops and abandoned their ancient and exquisite homes to new owners.

With this in mind, I was pleasantly surprised to read the lead article in the March issue of Touchstone. Joel Carillet writes of his visit there in December 2004 in The Return of the Suriani: A Visit to a Christian Minority in Turkey that Refuses to Die. Carillet found, to his surprise, not a dying community, but one that showed signs of rebounding, with people returning from Germany and Sweden, new construction at the monasteries and renewed hope for the future. He visited the Mar Yacub, Mar Gabriel and Deir Zafaran Monasteries, as well as the Church of the Holy Martyrs. The oldest monastery dates to AD 397. Some estimates now place the Syriac Christian population there at 5,000.

Part of the change is, of course, Turkey's push to join the EU. Europe is closely watching how the Turks treat their minority groups. In same cases, the government has even moved Kurdish families out of Syriac villages they had occupied. Tourism is increasing, and the monks are pleased and hopeful that many of the visitors are Turks who are learning (finally) of the Syriac Christian culture.

I like the following passage from the article:

Evening vespers were held in a room built in AD 512, making it one of the world's oldest functioning churches. Inside the stone walls darkness was broken, just barely, by two candles. The congregation of monks, nuns, and students--about 25 people--chanted together in Aramaic, the language of Jesus. The archbishop stood before the congregation wearing a robe that has changed little in over a thousand years. The entire setting was like having stepped out of a time machine, a lesson in the history of the church well before Christians ever made it to America and thought up things like seeker-friendly services.

But what struck me most was how they prayed: on their knees, face to the floor. It was a form of prayer that demanded something of the body and not just the mind. And it was also a reminder that when Islam was starting out, it borrowed much from Christianity. Except for the sign of the cross, which the congregants made between prostrations, and the presence of women in the same rows as men, this prayer could have been in a mosque.

If all goes well, I will visit this area myself in June. For more pictures from the Tur Abdin, go here.